New Book Looks into the Value of Religious Confession

- By Geoffrey Peters --

- 02 Feb 2022 --

“Religious Confession and Evidential Privilege in the 21st Century” seeks to spark discussion on the preservation of the confidentiality of confession while increasing accountability, especially in the case of the vulnerable.

Published December 17, 2021, Religious Confession and Evidential Privilege in the 21st Century, edited by Mark Hill QC and A. Keith Thompson, begins in Australia where the book was published by Shepherd Street Press, an imprint of Connor Court Publishing, and the School of Law of University of Notre Dame, and continues in Europe and America, with particular emphasis on the practice and protection of confession.

The paperback edition of the book is available through Amazon.com, Barnes and Noble and through the publisher, Connor Court Publishing.

In December 2017, an Australian Royal Commission published the findings and recommendations of a five-year investigation into Institutional Responses to Child Sexual Abuse. Among the Commission’s 189 recommendations was one that threatened sacred beliefs and practices of the Roman Catholic Church stating that laws on reporting sexual abuse of children “should exclude any existing excuse, protection or privilege in relation to religious confessions.”

In September 2020, the Vatican told Church leaders in Australia that while victims of sexual abuse should be encouraged to report abuse to the proper authorities, the seal of confession is not up for debate.

Unlike the other countries covered in the book, in Australia, freedom of religion or belief and the confidentiality of religious confession is not covered by the constitution or a bill of rights. And although guaranteed by the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights to which Australia subscribed, it has never been incorporated into law.

In Europe, confession is far more secure, as highlighted by chapters on how Italy, Norway and Sweden deal with the issue of confessional confidentiality.

Although no longer the state religion in Italy, the Roman Catholic Church operates under a concordat—a treaty between the government and the Vatican. It is further strengthened by “Europe’s commitment to privacy as a secular value which operates to protect religious confidences in Italy.”

In Scandinavian countries such as Norway and Sweden the right to religious confession is not only a given. Until recently, secular laws made any disclosure of religious confidences a criminal offence, although it is recognized that the protection of children is also a primary duty.

The section on the United States covers the priest/penitent privilege of American branches of the Orthodox Church, the Ukrainian Catholic Church and the Church of Scientology, in which an extensive overview is presented on the history of freedom of religion and priest/penitent privilege from the country’s colonial period through the adoption of the Bill of Rights to the present, including the difference between federal and state law in this regard.

The chapter on Scientology also describes the ways in which the practice of auditing (Scientology spiritual counseling) is analogous to confession in the Roman Catholic, Orthodox and Anglican tradition.

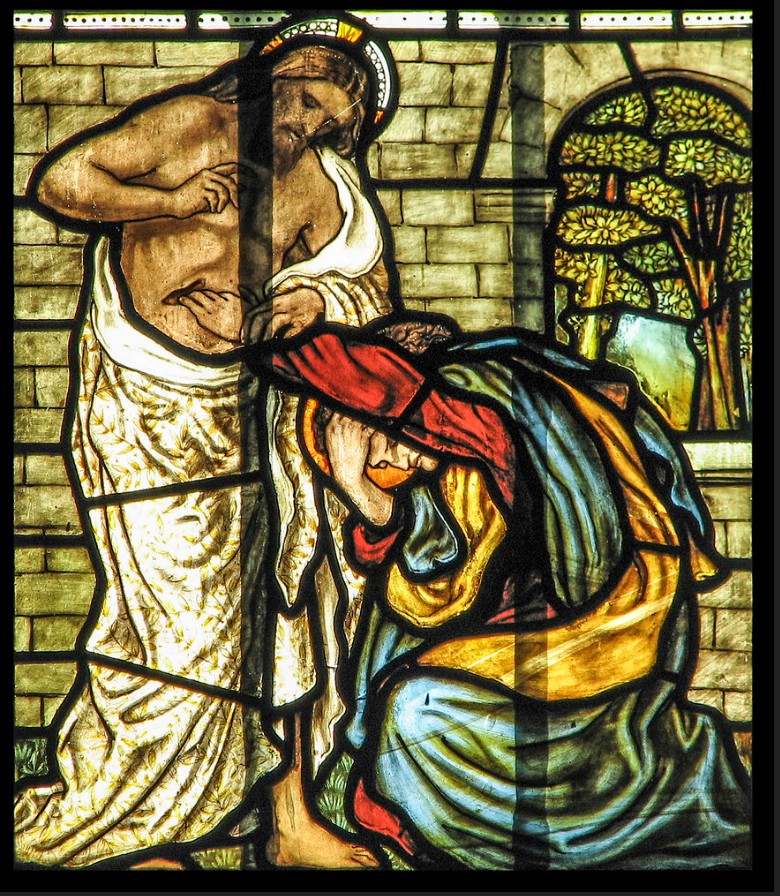

In the introduction to the book, the Right Reverend Rowan Williams, 104th Archbishop of Canterbury (2002–12), states “the purpose of the confessional discipline is the restoration of the penitent to the life of the community—with all the healing and reparation that might imply. When a priest hearing a confession imposes a penance, the priest is not looking backwards at an offence that needs to be covered over but forwards to a perhaps painful process of truthfulness and repairing of relation with God and with the human community. It is precisely the assurance of confidentiality that is supposed to allow the penitent to be honest, to bring into the open what may seem too shameful, too humiliating or shocking, to speak of. Where grave offence and lasting injury are confessed, serious steps must be imposed and demanded.”

In Scientology as well, the book states, “Personal responsibility is a main road through which Scientologists seek their spiritual freedom; responsibility which requires bettering one’s life and that of others.” Spiritual freedom requires that one unburned himself or herself of transgressions and take responsibility for their acts.

While a relatively new religion, “Scientology Churches have been called upon to establish time and again that Scientology is a bona fide religious practice in country after country.”