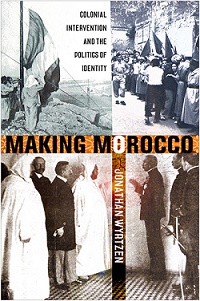

Jonathan Wyrtzen on ‘Making Morocco: Colonial Intervention and the Politics of Identity’

- By Joseph Preville --

- 15 Apr 2016 --

Making Morocco is a look into Morocco’s struggles of national identity in its colonial past.

Written by Joseph Preville and Julie Poucher Harbin for ISLAMiCommentary

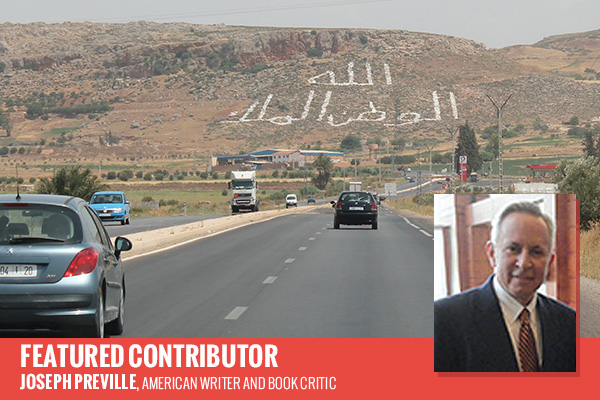

The motto of the Kingdom of Morocco is “Allah, al-Watan, al-Malik” (God, the Nation, the King). This motto was the spark for Yale University professor Jonathan Wyrtzen’s new book, Making Morocco: Colonial Intervention and the Politics of Identity (Cornell University Press, 2015).

Jonathan Wyrtzen on Making Morocco: Colonial Intervention and the Politics of Identity.[/tweetthis]

Enroute to begin his teaching job at Al Akhawayn University in Ifrane, Morocco in 2001, Wyrtzen noticed the motto painted on a hillside at the town of El Hajeb. He wondered how it came to be written on this hillside and what it said about Moroccan identity.

In Making Morocco, he offers an expansive way to look at Morocco’s colonial past (1912-1956); showing how “a constellation of Moroccan actors” interacted in the debates and struggles over national identity, including Jews, Berbers, and women.

This Moroccan mix of voices found expression in the Preamble to the 2011 Constitution: “The Kingdom of Morocco, a sovereign Muslim state attached to its national unity and territorial integrity, intends to preserve, in its plenitude and diversity, its one and indivisible national identity. Its unity, forged by the convergence of of its Arabo-Islamic, Amazigh [Berber], and Saharan-Hassanian components, is nourished by its African, Andalusian, Hebrew, and Mediterranean influences.” The constitution also recognized Tamazight (Berber) as an official language as “common patrimony of all Moroccans without exception” in addition to Arabic. Berber languages are spoken by 35-40% of Moroccans.

Today, Morocco is a country of nearly 34 million people; approximately 99% Muslim and 1% other (Christians, Jews, and Baha’i). There are between 4,000-8,000 Christians and 350-400 Bahais, according to the U.S. State Department’s Morocco 2014 International Freedom Report. While its Jewish population currently stands at about 5,000, before the establishment of Israel in 1948 some 250,000-300,000 Jews lived in Morocco — the largest in the Muslim world.

Wyrtzen is Associate Professor of Sociology, History, and International Affairs at Yale University. Educated at The University of Texas at Austin, Hebrew University of Jerusalem, and Georgetown University, his scholarly work has appeared in Oxford Encyclopedia of the Modern World, The Journal of Modern History, and the International Journal of Middle East Studies. He discusses the themes of his new book in this interview.

Tell us more about the pillars of Moroccan identity.

The official triptych motto —”God, Nation, and King” — actually references four pillars around which Moroccan identity is defined. God (Allah) signals the importance of Islamic religious identity, and the reference to the King (Malik) privileges the unifying role of the reigning Alawite monarchy. The term Nation (Watan) encompasses two other features. One is a sense of ethnic identity (the motto is written in Arabic) and the other is the notion of Moroccan territory.

In the book I argue that colonial intervention activated the political salience of these pillars — religion, ethnicity, territory, and the monarchy — which have since been at the center of struggles over Moroccan identity. While distinct, the four pillars overlap in complex ways. For example, questions related to official Moroccan Islam, the position of the Jewish minority, the role of the king as “Commander of the Faithful,” Morocco’s territorial claims over Western Sahara, and recent renegotiations of Arab and Berber identities are all interconnected.

How did you become interested in the history of Morocco?

My specific interests in Moroccan history were triggered by events taking place during that time in the early 2000s. King Mohamed VI succeeded to the throne after his father’s death in 1999. In October 2001, a month after we got to Morocco, he traveled to a site near his mother’s home in the Middle Atlas, close by where we were based, to announce the creation of the Royal Institute for Amazigh (Berber) Culture. I became intrigued by this shift towards an multi-ethnic official discourse of Moroccan identity fifty years after a nationalist independence struggle that emphasized the country’s Arab and Islamic heritage. This led to an interest in how the colonial period in Morocco had impacted questions related to religious and ethnic identity and how the monarchy had survived and thrived through colonization and decolonization.

How is your book is different from others written on Moroccan history?

My major aim was to write a post-colonialist and post-nationalist history. The initial goal for nationalists in North Africa was to “decolonize history;” revising the colonial histories written by the French. This has meant treating the protectorate (1912-56) as a parenthesis in Moroccan history and emphasizing an uninterrupted continuity between the pre- and post-colonial periods. In the trajectory of this nationalist story, the “Moroccan nation” is a unitary actor across this divide that steadfastly resisted colonization and heroically achieved independence in 1956.

In contrast, I argue that European colonial intervention constituted a profound rupture in Moroccan history and that, at a deep level, the protectorate has to be factored into our understanding of the country’s 20th and 21st century history. I focus on processes catalyzed by colonial intervention and state-building that transformed Moroccan identity in fundamental ways.

As a sociological history, this book is different in using a more explicit theoretical model than is usual in other histories. The book’s governing concept of a “colonial political field” provides a means through which to think about how colonial military conquest delineated the physical space of Morocco, how the colonial state tried to legitimize European rule as “protecting” the Moroccan sultan, and how it politicized ethnic and religious identity by creating separate Arab, Berber, Muslim, and Jewish educational, administrative, and judicial structures. My focus is not on any single actor in the story — the King, the French, the urban nationalists, or rural populations — but on how all of these groups interacted together within the colonial political field. In this respect, the book represents a new big picture synthesis of Morocco’s colonial history that incorporates previously excluded perspectives from the rural margins, from the religious minority, and from a range of urban and rural Moroccan women.

This is an extremely exciting time to be working on North Africa and in colonial/postcolonial studies more broadly, as there is a large, new cohort of scholars reengaging older questions in the literature and breaking new ground.

Why do you think the voices of minorities – Berbers, women, and Jews – have been “virtually silent in the existing historiography” ? How are minorities and women treated today?

One of the obvious reasons these voices have been less represented is that historians typically base their work on written documents, and most Berber-speakers and women in Morocco have historically been illiterate. They have not left much in the way of a written record, so it is hard to find other types of sources from which to write history from their perspectives.

There is also a political reason. During the independence struggle in Morocco from the 1930s-50s and in other colonized societies in North Africa and elsewhere, the initial priority for nationalist elites was to justify their claims for popular sovereignty. In Morocco, this meant undercutting French claims about a historical ethnic cleavage and antagonism between Arabs and Berbers and a perennially weak Moroccan state that could never unify the country. The alternate historical narrative that urban Arabic-speaking Moroccan men (and a handful of elite women) propounded emphasized how Islam, Arabic culture and language, and Muslim dynasties had unified a single Moroccan nation over the course of more than 1300 years.

Ethnic (Arab versus Berber), religious (Muslim versus Jewish), and gendered boundaries were highly politicized during the colonial period, and Berbers, Jews, and women shaped Moroccan identity as objects of struggles among French administrators, the Moroccan king, and Arab nationalists. One of my priorities, however, was to demonstrate how these groups were also agents that were struggling to shape ideas about Moroccan identity during this pivotal period. This required creatively using different genres including oral history, poetry, song, and editorial debates by Moroccan Jews in newspapers to voice these perspectives.

One of the major developments of the past couple of decades has been how the Amazigh (Berber) movement and women’s movements have fought to revise Arab- and male-centric accounts of Moroccan history. Morocco’s Jews, though a tiny minority, also play an outsized role in current-day perceptions of Moroccan identity. The presence of Morocco’s Jews in the country, outside of the country, and in Moroccan memory are integrally connected to the type of tolerant, pluralistic form of Moroccan Muslim order promoted by the monarchy.

In January 2016, Muslim leaders defended the rights of religious minorities in Muslim majority countries in the “Marrakesh Declaration.” It appears to have originated in Morocco. Why did the King embrace the ideas in it and make it a priority for Morocco? Going forward, do you think this document will become influential and transformative within and outside of Morocco?

Yes, the conference was organized at the behest of the King by the Moroccan Ministry for Religious Endowments and Islamic Affairs in cooperation with a United Arab Emirates initiative, the Forum for Peace. The declaration uses Islamic precedents, including the Charter of Medina, to forcefully assert that Muslim-majority states and civil society groups (including intellectuals, artists, and NGOs) must protect and affirm an inclusive notion of citizenship guarding the rights of religious minorities.

These ideas about tolerance and plurality are at the core of a brand of Moroccan Islam that the King and Ahmed Toufiq, Morocco’s minister for Islamic Affairs, have been cultivating and promoting for more than a decade. Within Morocco, then, the declaration is not a radically new shift. The new 2011 Moroccan constitution makes a similar affirmation. The free exercise of religion is protected for all by a state for which the official religion is Islam, but there is ambivalence about how far the limits of that free exercise go. It does not explicitly protect the right of non-Muslims to try to convert Muslims. It also does not protect the rights of Moroccans to publicly demonstrate agnosticism or unbelief (i.e. publicly breaking the fast during Ramadan).

Despite some ambiguities in how it gets implemented, though, I do think the Marrakesh Declaration’s public and deliberate call for protecting religious minorities is significant and hopefully will be influential outside of Morocco too. For me, it was profoundly ironic, after repeated calls since 9/11 in the West for “moderate Muslims” to stand up against “radical Islam,” to have that Marrakesh conference and the declaration happening at the very moment Donald Trump was publicly calling for all Muslims to be banned from entering the U.S. following the San Bernardino shootings. I think, therefore, that the Marrakesh Declaration is transformative in how it is juxtaposed not only against examples of intolerance elsewhere in the Muslim World, but perhaps more poignantly against intolerance in the United States and Europe.

Morocco’s neighbor, Tunisia, has been lauded by many to be the only democracy, while fragile, to emerge in the regional post-Arab Spring. Did Morocco come out of the Arab Spring unscathed? Even with a King, does Morocco aspire to be a model of Arab-Islamic democracy? Is it succeeding?

I was in Morocco working on this book in 2011, and it was a fascinating time to watch what was happening in Tunisia, Egypt, and then the other countries in the region. The Arab Spring began to directly affect Morocco when the February 20th Movement organized protests in Rabat and other cities denouncing corruption, calling for economic and educational reforms, and calling for democratic constitutional reforms. Having learned from the examples of Ben Ali and Mubarak, the King reacted very quickly, going on television on March 9th to announce his own plan for a comprehensive constitutional reform. The new constitution was drafted over the next couple of months by a royal commission then approved by a national popular referendum in July.

Morocco was unique in that the central demands during its 2011 protests was not for the “downfall of the regime,” as in other countries in the region, but for a “king who reigns but does not rule.” In many respects, the new constitution provides for this transition to a genuine constitutional monarchy, formally shifting more power to the Prime Minister and the government.

In the end, however, Morocco came out of the Arab Spring changed and unchanged. The monarchy brilliantly executed and continues to execute a public relations strategy that melds Islam, democracy, human rights, pluralism, and tolerance, but there is still a gap between the formal and informal structuring of power in Morocco, five years since the implementation of the new constitution. Despite changes on paper, the makhzan, the deep state network surrounding the king, still exercises de facto real power. Given the continuing tumult in the region, the infamous “shwiyya b’shwiyya” (little by little) Moroccan approach, leveraging the relative benefits of incremental reform against the specter of revolution (Algeria in the 1990s or Libya and Syria in the present), still works.

In Morocco, the fragility of the Tunisian democratic transition is used as an argument against change. For most people, it seems preferable to have stability over change, given the worst-case scenarios of the latter that have played out over the past five years elsewhere in the region.

Can you recommend a few books on the history of Morocco?

This is a hard question as I have dozens of books I want to recommend! For a good overview of Moroccan history, I recommend Susan Gilson Miller’s A History of Morocco or C.R. Pennell’s Morocco Since 1830: A History. On questions related to religious and racial minorities, Aomar Boum’s recent book Memories of Absence: How Muslims Remember Jews in Morocco is fantastic as is Chouki El Hamel’s Black Morocco: A History of Slavery, Race, and Islam. For readings on the colonial period, I recommend two books that capture Fes during the 1940s-50s: Fatima Mernissi’s memoir, Dreams of Trespass: Tales of a Harem Girlhood and Paul Bowles’ novel, The Spider’s House. That is a start, and readers should feel free to email me for more recommendations!

ISLAMiCommentary is a public scholarship forum that engages scholars, journalists, policymakers, advocates and artists in their fields of expertise. It is a key component of the Transcultural Islam Project; an initiative managed out of the Duke Islamic Studies Center in partnership with the Carolina Center for the Study of the Middle East and Muslim Civilizations (UNC-Chapel Hill). This article was made possible (in part) by a grant from Carnegie Corporation of New York. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author(s).

This article originally appeared on ISLAMiCommentary.