“Lives in Common:” Israeli scholar Menachem Klein on Israel and Palestine

- By Joseph Preville --

- 27 Mar 2015 --

Menachem Klein discusses his new book Lives in Common and the prospects of Peace between Israel and Palestine with ISLAMiCommentary.

Written by Joseph Preville and Julie Poucher Harbin for ISLAMiCommentary

“Only few Israelis and Palestinians see their counterparts as equal human beings with the same collective and individual rights. The Israeli elections may bring new political leadership, but this leadership should introduce this missing perspective, not follow the right wing governments in seeing the Palestinians and other Arab – Muslim societies as an existential threat to us. ” — Menachem Klein

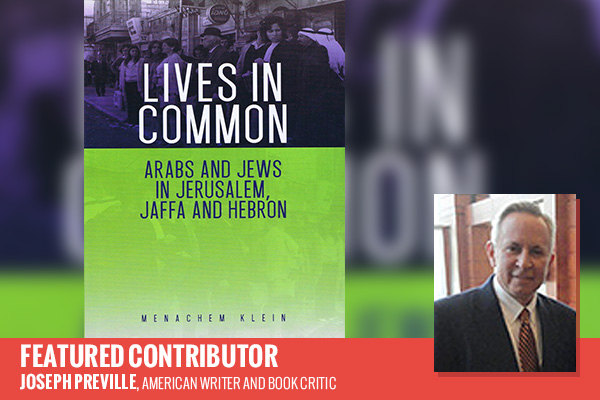

Once upon a time, Jews and Arabs in Palestine were partners, neighbors, and friends. Israeli scholar Menachem Klein reminds us of this historical fact in Lives in Common: Arabs and Jews in Jerusalem, Jaffa and Hebron (Hurst & Company, 2014). And, he explains how the shared native identity between Jews and Arabs was shattered by the “Zionist-Palestinian conflict of 1948.”

Once upon a time, Jews and Arabs in Palestine were partners, neighbors, and friends. Israeli scholar Menachem Klein reminds us of this historical fact in Lives in Common: Arabs and Jews in Jerusalem, Jaffa and Hebron (Hurst & Company, 2014). And, he explains how the shared native identity between Jews and Arabs was shattered by the “Zionist-Palestinian conflict of 1948.”

He postulates that the “old Jewish-Arab identity” could be reframed for today, but says “strong forces seek to sabotage this possibility by deepening the fissure between Jews and Arabs and seeking exclusive ownership of the land.”

Klein is a senior lecturer in the Department of Political Studies at Bar-Ilan University, Israel, a Senior Fellow in Bruno Kreisky Forum for International Dialogue, and a board member of the Palestine – Israel Journal. He has also served as a visiting professor at MIT and as a fellow at Oxford University. Since 1996 Klein has been active in many unofficial negotiations with Palestinian counterparts. In 2000 he was an adviser for Jerusalem Affairs and Israel-PLO Final Status Talks to the Minister of Foreign Affairs, S. Ben-Ami, and a member of an advisory team operating in the office of Prime Minister Ehud Barak. In October 2003 Klein signed, together with prominent Israeli and Palestinian negotiators, the Geneva Agreement – a detailed proposal for a comprehensive Israeli-Palestinian peace accord.

Klein is the author of many books, including, A Possible Peace Between Israel and Palestine (Columbia University Press, 2007) and The Shift: Israel-Palestine from Border Struggle to Ethnic Conflict (Columbia/Hurst, 2010).

He discusses Lives in Common and prospects for peace in this interview:

Why did you choose to use cities as a vehicle or focal point for exploring the historical relationship between Palestine’s Arabs and Jews? And, why in particular, Jerusalem, Jaffa and Hebron?

Jerusalem and Hebron, two mountain cities and the two holiest cities in Palestine, hafve been contrasted with Jaffa, the worldly coastal city. Each of these cities is home to a Palestinian community with its own character and status, and each of them is also home to a Jewish community of a different sort. The conflict between Israeli Jews and Palestinian Arabs is different in each of these cities, only about 40 miles distant from each other, yet it is also much alike. In the same way, the Jews and Arabs in each of these cities have evolved relationships that, while similar in some ways, are different in others.

Jerusalem and Hebron, two mountain cities and the two holiest cities in Palestine, hafve been contrasted with Jaffa, the worldly coastal city. Each of these cities is home to a Palestinian community with its own character and status, and each of them is also home to a Jewish community of a different sort. The conflict between Israeli Jews and Palestinian Arabs is different in each of these cities, only about 40 miles distant from each other, yet it is also much alike. In the same way, the Jews and Arabs in each of these cities have evolved relationships that, while similar in some ways, are different in others.

How does your book challenge “the accepted scholarly view” on the relationship between Palestine’s Jews and Arabs at the end of the 19th and the beginning of the 20th century?

Unlike the approach generally taken by historians of the Jewish national movement or its Palestinian rival, this book’s starting point is not an event that was constitutive of Zionism or Palestinian nationalism. My narrative starts in the end of the nineteenth century, when a local Palestinian identity began to form, an identity in which Jews and Arabs were partners. It did not arrive from the outside, like Arab nationalism and Zionism, but rather grew out of the daily lives of the country’s inhabitants during a rapidly modernizing and westernizing period, in which the authority of the Ottoman regime was growing weaker. The voice of this identity has not yet been heard.

How intertwined were Jewish and Arab lives before the establishment of Israel in 1948?

Jews and Arabs in mixed cities shared much of their everyday life – in their mixed neighborhoods, the markets, holy sites, religious festivals, their languages, coffee shops, and sometimes also in schools and mixed marriages. My chapters are composed of small scraps of the fabric of life, with all their contrasts and different paths.

If Jews and Arabs were once connected to place, did their initial differences with each other emerge mainly around religion or culture or demographics?

Of course there were differences between them; their common lives was limited. The level of mixing was different in each sphere. A joint language was something they shared. There were mixed neighborhoods. There was less mixing in the education systems and in marriage.

Religion divided them, but this division was not total. Their lives in common included several aspects of religion and culture. Jews and Muslims shared holy sites and to a certain extent also religious festivals. Jews participated in Nabi Musa festival, and both religions shared holy sites such as Nabi Samueil and Simon the Pius. Indeed there were clashes at the Wailing Wall in 1929, which spread to Hebron and the rest of the country, but they (clashes) were spurred by the growing national conflict between Zionism and the Palestinian national movement, not due to problems in living together beforehand.

How did the emergence of Israel change the relationship between Jews and Arabs?

At its inception, the Zionist – Palestinain conflict in the late 20’s and 30’s was a disturbance in this local identity. In the mid-1930s, and even more so after World War II, the conflict expanded and itself became routine. The Zionist-Palestinian conflict of 1948 finally defeated the local identities that had previously flourished, in different ways, in Jaffa, Jerusalem, and Hebron. For this reason, Part I of the book is called “Connected to Place.” The second part is entitled “Connected by Force.” It describes the development of relations on the streets of Jaffa, Jerusalem, and Hebron after 1948. To offer a broad generalization, the two national movements at this time were preoccupied not only with nation-building but also with expunging or taking over the previous identity. The Israeli victory of 1948 was redoubled in the war of 1967, fixing Israeli power as a shaper of identity. In this second part of the book I describe how force shapes the streets of Jaffa, Jerusalem, and Hebron — not only their present form, but also their takes on the past — that is, how they depict the period prior to 1948.

Most people understand the labels “Israeli Jews” and “Palestinian Arabs.” In fact it fits neatly in the conflict narrative of “Israeli Jews vs. Palestinian Arabs.” What about the label “Arab Jew”? In your book you write about Arab Jews. What happened to that identity?

Jewish-Arab identity in its original form no longer exists. Anyone who advocates such an identity today needs to grant it new meaning. If Israel were to accept the Arab League’s peace initiative, Prince Turki al-Faisal of Saudi Arabia has said, “We will start thinking of Israelis as Arab Jews rather than simply as Israelis.” He does not and cannot propose to turn the clock back and do away with nation-states as prime shapers of identity. A contemporary Jewish-Arab identity, he maintains, means close ties between Israel and the Arab countries: “One can imagine the integration of Israel into the Arab geographical entity. One can imagine not just economic, political and diplomatic relations between Arabs and Israelis but also issues of education, scientific research, combating mutual threats to the inhabitants of this vast geographic area.” (Paul Taylor, “Saudi Prince offers Israelis a vision of Peace,” NYT, 02/01/2008). This indicates a possibility of reframing the old Jewish-Arab identity in a way that would make it appropriate for the present.

Where do you place “Israeli Arabs” in the conflict narrative?

The conflict developed as an ethnic conflict in particular since 2000. During the Oslo years it was moving towards a border struggle, but with the second Intifada it turned back into an ethnic conflict. I discuss this turn in my book The Shift. The ethnic conflict of today includes the Israeli – Palestinians [Palestinians that are full Israeli citizens living outside 1967 occupied territories]. However their status as Others, as belonging to the Other ethnicity is different than Palestinians living under the Israeli occupation. Since the conflict became mainly a conflict between two ethnic groups residing on the same land, citizenship less defines who is the Other. The Other is defined along his or her ethnic belonging not according citizenship. Israeli Jews, therefore, are inclined to see their Palestinian fellow citizens as members of their rival group rather than of their state. The shift from border to ethnic conflict has an impact also on Israeli Palestinians. More than ever before, they struggle with their brothers and sisters in the occupied territories against “Israeli – Jewish ethnic superiority”; i.e. the Israeli legal system and power structure provides Jews privileges over non-Jewish citizens, in this case Palestinians.

Do Palestinian Arabs and Israeli Jews have more in common than not in common?

Compared to the past they have almost nothing in common. Israeli society shifted and moved away from the Oslo period of openness and toward ethnocentrism defined as “The Jewish State.” Simultaneously, the Palestinians also shifted to prefer ethnicity over citizenship. Today less and less Palestinians see Jews as indigenous people, natives of Palestine. Each side sees the other ethnicity as an invader. As I said before, it can be different. Of course there is no way to go back to prior 1948 era. I am realistic. But there is a way to form up a better future, to build coexistence between nations and cultures — enjoying equal status and mutual respect and freedom.

Do you agree with Amos Oz that “There is a growing sense that Israel is becoming an isolated ghetto, which is exactly what the founding fathers and mothers hoped to leave behind them forever when they created the state of Israel” (Roger Cohen, “What Will Israel Become,” NYT, (12/20/2014) ?

Sure, he is right. This is one of the Israeli – Zionist major tragedies. We, Israeli Jews, succeeded in building a strong state and modern Hebrew culture, but are isolated and occupied by our own siege mentality. Jews outside Israel, in the past as well as in the present, integrate in countries where they live. Rich dialogue and mutual influence developed between those Jews and their neighbors. Unfortunately the case of Israel and its Arab neighbors is very different. This should change.

So this brings us to the age old question — How can historical wounds be healed? By understanding history better? By the actions of local, national, or world political actors? Grassroots efforts? A new generation?

Wherever human beings are considerate of each other when they meet, there is a possibility of healing even wounds like those incurred by the refugees of 1948 and 1967. Indeed, there is no way to return to the common native identity that prevailed in Palestine before 1948. However, interaction between equal human beings who share the same city — or country — can enable coexistence between nations and enable them to cope with past wounds.

Do you feel that, at the highest political levels, this “being considerate” isn’t happening anymore? Do you see the Israeli elections changing this toxic atmosphere for better or worse? Any concrete ideas on how to get to a place of peaceful coexistence again ? Unfortunately this is not being considered at the highest political levels. Only few Israelis and Palestinians see their counterparts as equal human beings with the same collective and individual rights. The Israeli elections may bring new political leadership, but this leadership should introduce this missing perspective, not follow the right wing governments in seeing the Palestinians and other Arab – Muslim societies as an existential threat to us.

ISLAMiCommentary is a public scholarship forum that engages scholars, journalists, policymakers, advocates and artists in their fields of expertise. It is a key component of the Transcultural Islam Project; an initiative managed out of the Duke Islamic Studies Center in partnership with the Carolina Center for the Study of the Middle East and Muslim Civilizations (UNC-Chapel Hill). This article was made possible (in part) by a grant from Carnegie Corporation of New York. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author(s).

This article originally appeared on ISLAMiCommentary.