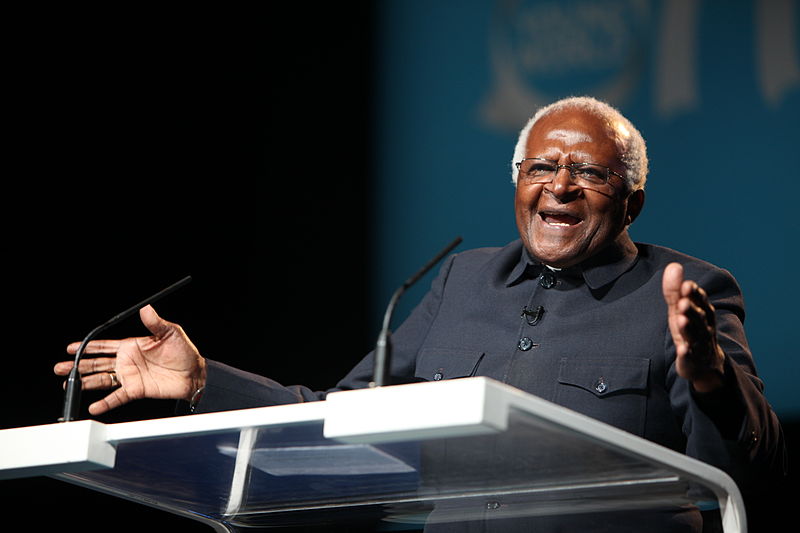

Profiles in Faith: Archbishop Desmond Tutu

- By Sam Field --

- 16 Jun 2021 --

Introduction

Impelled by his faith to confront widespread human rights abuse in South Africa, Archbishop Desmond Mpilo Tutu gained worldwide fame in the 1980s for his role in fighting and ending apartheid, one of the 20th century’s worst crimes against humanity. Often seen in public in his trademark purple cassock, Tutu went on to become one of South Africa’s most enduring voices for social change and poverty alleviation.

Impelled by his faith to confront widespread human rights abuse in South Africa, Archbishop Desmond Mpilo Tutu gained worldwide fame in the 1980s for his role in fighting and ending apartheid, one of the 20th century’s worst crimes against humanity. Often seen in public in his trademark purple cassock, Tutu went on to become one of South Africa’s most enduring voices for social change and poverty alleviation.

Tutu was elected and ordained as the first Black to head the Anglican Church in South Africa. In 1995, a year after apartheid ended, South African President Nelson Mandela appointed him to head the country’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission. The body sought to unify South Africans by granting immunity to those who confessed to crimes committed in the name of apartheid or against it between 1960 and 1993.

After apartheid, Tutu named South Africa “Rainbow Nation,” a reference to its multicultural population. He is one of the country’s leading elder statesmen and spiritual leaders.

In His Own Words

“There are different kinds of justice. Retributive justice is largely Western. The African understanding is far more restorative — not so much to punish as to redress or restore a balance that has been knocked askew.” — Archbishop Desmond Tutu, in “Recovering From Apartheid,” The New Yorker, November 18, 1996

“God looked around and said, ‘Here is this strange-looking guy with a big nose and Tutu is a relatively easy name to remember. Let’s see what he can do.’ I was grabbed by the scruff of the neck and was fortunate that God allowed me to have so many fellow workers who helped us.” — Archbishop Desmond Tutu, in a 2013 interview at the University of North Florida, Jacksonville, where he was a visiting scholar and keynote speaker at the Martin Luther King Jr. Scholarship Luncheon.

“I am ashamed to call this lickspittle bunch my government.” — Archbishop Desmond Tutu, in The New York Times, October 6, 2014, referring to the South African government’s refusal to grant the Dalai Lama a visa to visit South Africa to attend a gathering of Nobel laureates. The refusal, evidently under pressure from the government of the People’s Republic of China, marked the third time since 2009 that the Tibetan spiritual leader had been denied entry to South Africa. In 2011, he wanted to visit South Africa to celebrate Archbishop Tutu’s 80th birthday.

“I give great thanks to God that he has created a Dalai Lama. Do you really think, as some have argued, that God will be saying: ‘You know, that guy, the Dalai Lama, is not bad? What a pity he’s not a Christian?’ I don’t think that is the case—because, you see, God is not a Christian.” — Archbishop Desmond Tutu, in a June 2, 2006, BBC article.

“If the church, after the victory over apartheid, is looking for a worthy moral crusade, then this is it: the fight against homophobia and heterosexism.” — Archbishop Desmond Tutu, in his foreword to the 1997 book, Aliens in the Household of God: Homosexuality and Christian Faith in South Africa.

“On many occasions, back home in South Africa, when ghastly things were happening in our struggle against apartheid, often the cry went out from our people, ‘God, where are you? God, do you care? God, do you see?’ And we would tell our people that wonderful story in the book of the prophet Daniel, of the God whose servants had been cast into a fiery furnace. And then, and then, God didn’t stand at a safe distance giving useful advice — ‘Guys, when you go into a fire, it would probably be sensible to put on protective clothing.’ No, fantastically, God entered the fiery furnace, and was there side by side with God’s servants in their anguish and agony, because this God was Emmanuel, ‘God with us,’ God with us in our suffering, in our oppression and in our anguish.” — Archbishop Desmond Tutu giving a sermon at the Washington National Cathedral on September 11, 2002, on the first anniversary of the 9/11 terrorist attacks.

“I would suggest that the United States could benefit from something like a Truth and Reconciliation Commission, where people would be able to tell their story. I am aware that in many African Americans there is a pain that is often not acknowledged, which, perhaps, if allowed to be articulated, would lance a boil. This country has really not yet come to terms with the legacy of slavery. It has not come to terms with the legacy of the confiscation of land of the indigenous people. The pains of those two experiences are deeply embedded in the psyche of those who were the victims.” — Archbishop Desmond Tutu, in a 2013 media at the University of North Florida, where he was the keynote speaker at the Martin Luther King Jr. Scholarship Luncheon.

“At home in South Africa I have sometimes said in big meetings where you have Black and White together: ‘Raise your hands!’ Then I have said: ‘Move your hands,’ and I’ve said, ‘Look at your hands — different colors representing different people. You are the Rainbow People of God.’” — Archbishop Desmond Tutu, quoted by the BBC in December 1991.

“One time I was in San Francisco when a lady rushed up, very warmly greeted me, and said, ‘Hello Archbishop Mandela.’ Sort of getting two for the price of one.” — Archbishop Desmond Tutu, quoted by the BBC in March 2004.

The Stories Others Tell

“Tutu was saluted by the Nobel Committee for his clear views and his fearless stance, characteristics which had made him a unifying symbol for all African freedom fighters. … Despite bloody violations committed against the Black population, as in the Sharpeville massacre of 1961 and the Soweto rising in 1976, Tutu adhered to his nonviolent line. Yet he would not blame Nelson Mandela and his supporters for having made a different choice. The Peace Prize award made a big difference to Tutu’s international standing, and was a helpful contribution to the struggle against apartheid. The broad media coverage made him a living symbol in the struggle for liberation, someone who articulated the suffering and expectations of South Africa’s oppressed masses. There are many indications that Tutu’s Peace Prize helped to pave the way for a policy of stricter sanctions against South Africa in the 1980s.” — Norwegian Nobel Institute

“Bishop Desmond Tutu, the winner of this year’s Nobel Peace Prize, returned home today to a joyous airport welcome. His supporters greeted him with hugs, impromptu dancing and songs about South Africa’s ‘liberation.’ White police officers made no move to interrupt the celebrations. At a news conference later, Bishop Tutu made no departures in either tone or substance from two familiar themes: that his country is heading for violent ‘catastrophe’ if the White authorities refuse to negotiate with Blacks, and that Reagan Administration policy in South Africa has been, in his view, an ‘unmitigated disaster.’ … At a news conference, Bishop Tutu said the most important consequence of his winning the award was ‘helping to focus the attention of the world on South Africa slightly more than would have been the case otherwise.’ … His award, he said, was ‘for the little people of South Africa, the people who are getting their noses rubbed in the dirt every day.’” — The New York Times, October 19, 1984.

“This year the Nobel Committee has reaffirmed a broad, humanist definition of peace. By awarding its prize to South Africa’s Bishop Desmond Tutu, the committee has not only honored and encouraged nonviolent struggle against apartheid, it has implicitly proclaimed that peace is not submission. Peace is not paralysis, it is not resignation, it is not haggles between nations for mutual advantage, it is not statesmen flying around the world making pompous, well-publicized speeches. It is dedication to the cause of the downtrodden without killing, without trampling. Bishop Tutu said it clearly and firmly. ‘We are struggling not to oppress somebody else, but in order to free everybody.’ And he told his compatriots, ‘Be nice to Whites, they need you to rediscover their humanity.’” — The New York Times, October 19, 1984.

“The Truth and Reconciliation Commission of South Africa has put the spotlight on all of us. … In its hearings, Desmond Tutu has conveyed our common pain and sorrow, our hope and confidence in the future.” — South African leader and Nobel Laureate Nelson Mandela on Archbishop Desmond Tutu’s role in helping restore justice through the Truth and Reconciliation Commission following the end of apartheid.

“Tutu’s theology was influenced by his strong moral biblical conviction on human equality in the Holy Bible (Galatians: 3:28, ‘There is neither Jew nor Greek, there is neither bond nor free, there is neither male nor female: for ye are all one in Christ Jesus’). To him, the White Afrikaans must realize the land of South Africa originally belongs to the Blacks despite their introduction of Christianity from Europe. Hence, there is a need to reconcile both the Bible and the land for a peaceful existence.” — Alexander Kokobili, The Evangelic Theological Faculty, Charles University in Prague, Czech Republic, in an April 2019 article in the Evangelical Journal of Theology, “An Insight on Archbishop Desmond Tutu’s Struggle Against Apartheid in South Africa,” page 124.

“Tutu sees humans as created for community and draws on African spirituality by using the theme of ubuntu to reinforce an ethic of interconnection where our humanity is caught up in that of all others. … Tutu’s pioneering, practical use of the imago dei motif to demand the rights of an oppressed group revealed that apartheid was, at heart, a theological problem. Instead of a divine monarch who dominates within God-ordained hierarchical structures, he models an egalitarian model of mutuality where people are free for each other in healthy relationships. Tutu’s ability to link God-images with concrete social behaviors enabled him not only to theologically legitimate the anti-apartheid struggle as a Christian imperative but has continued in relation to emerging human rights issues in churches such as the status of LGBTIQ+ people. He rethinks reconciliation as an ongoing participatory social task with God to help God’s children become more fully human.” — Extract from a 2019 book, Freedom of Religion at Stake: Competing Claims Among Faith Traditions, State and Persons. “Religiosity in South Africa and Sweden: A Comparison,” by Hennie Kotzé.

A Life in Brief

Desmond Tutu was born in 1931 in Klerksdorp, a city in South Africa’s North West province. He once described the section of society in which he grew up as “deprived, discriminated against, oppressed and marginalized,” and pointed out that what attracted him later in his life to Jesus Christ was “how he identified with those who belonged to such a group.”

The son of a schoolteacher, Tutu wanted to become a physician but couldn’t afford medical school. He trained as a teacher instead and taught for three years at a high school before studying theology. He was ordained as a priest in 1960 and he earned a master’s degree in theology from King’s College in England in 1966. He was appointed the first Black dean of St. Mary’s Cathedral in Johannesburg in 1975.

Tutu was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 1984 for his work to end apartheid in South Africa.

In 1986, he became the Anglican Archbishop of Cape Town. Tutu was also the first Black General Secretary of the South African Council of Churches, an organization founded in 1968 to promote the liberation struggle on religious and moral grounds.

He went on to become chairman of South Africa’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission, which investigated apartheid-era human rights abuses in the country.

Tutu’s long-standing resistance against apartheid and his unrelenting defense of Black civil rights in South Africa are the defining features of his career as a cleric and human rights activist. A prolific author, Tutu began his retirement from public life on October 7, 2010, his 79th birthday.

Since then, he has continued his efforts to combat worldwide poverty, HIV/AIDS, climate change, misogyny and homophobia.

Achievements We’ll Remember

• 1972-75: Tutu served as associate director of the World Council of Churches, whose mission is to unite Christian denominations in a spirit of mutual tolerance and harmony.

• 1975: Tutu became dean of St. Mary’s Cathedral in Johannesburg, earning the distinction of being the first Black South African to be appointed to the position.

• 1978: Tutu was appointed General Secretary of the South African Council of Churches, a multifaith organization that openly opposed apartheid. Tutu uses his position to galvanize nonviolent protests and international economic boycotts against the South African regime.

• 1984: Tutu won the Nobel Peace Prize “for his role as a unifying leader figure in the non-violent campaign to resolve the problem of apartheid in South Africa.”

• 1985: As anti-apartheid revolt spread across townships in South Africa, Tutu was appointed the first Black bishop of the Anglican Church of Johannesburg.

• 1986: Tutu was appointed Anglican Archbishop of Cape Town, the primate of South Africa’s Anglican Church, which had 1.6 million members at the time.

• 1989: Tutu shared the Third World Prize, conferred on individuals or institutions for their exceptional roles in the development of Cold War-era “Third World” countries, especially in economic, social, political and scientific fields.

• 1989: South African President Nelson Mandela appointed Tutu head of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, which probed apartheid-era human rights abuses and offered legal immunity to those who confessed to their crimes.

• 2005: Tutu was awarded the Gandhi Peace Prize in India.

• 2013: Tutu won the Templeton Prize for helping inspire people across the world by promoting forgiveness and justice. The prize honors a living person “who has made an exceptional contribution to affirming life’s spiritual dimension.”

The Religion He Leads

As Archbishop of Cape Town, Desmond Tutu was primate of the Church of the Province of Southern Africa (now the Anglican Church of Southern Africa).

Despite its global communion, Anglicanism does not have a worldwide juridical authority, and each province governs itself. The Archbishop of Canterbury, in the United Kingdom, is however, the Anglican Communion’s spiritual leader and “focus of unity.”

The Anglican Communion describes itself as “Protestant yet Catholic,” and “deeply grounded in the Early Church and the traditions and beliefs which have grown with Christianity from its beginnings, just like the Roman Catholic or Eastern Orthodox churches.”

The foundational prayer book of Anglicanism is the Book of Common Prayer, which the Archbishop of Canterbury created in 1549 by translating Latin Catholic liturgy into English and injecting Protestant reform theology into the prayers. Considered one of the great works of literature, the book has influenced the English language as well the liturgies of other Christian denominations, especially marriage and burial rites.

MORE PROFILES IN FAITH:

Mr. David Miscavige, Ecclesiastical Leader of the Scientology Religion

(Jan. 19, 2022)

Russell M. Nelson, President of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (Jan. 6, 22022)

Talib M. Shareef, Imam of Masjid Muhammad (Sept. 24, 2021)

Rabbi David Nathan Saperstein (September 5, 2021)

Neville Callam, Baptist World Alliance (August 23, 2021)

Patriarch Bartholomew Bridges East-West Christian Divide (August 12, 2021)

Paula Clark: First Woman and First African American to Lead the Episcopal Diocese of Chicago (July 28, 2021)

Wilton Cardinal Gregory: First African American Cardinal (July 21, 2021)

Hindu Guru Mata Amritanandamayi (July 8, 2021)

Rabbi Jonathan Sacks (July 1, 2021)

Pope Francis (June 23, 2021)

Archbishop Desmond Tutu (June 16, 2021)

Episcopal Bishop Michael B. Curry (June 9, 2021)

Thich Nhat Hanh, Father of Engaged Buddhism (June 2, 2021)

Ayatollah Al-Sayyid Ali Al-Huseinni Al-Sistani (May 26, 2021)

Justin Welby, the 105th Archbishop of Canterbury (May 19, 2021)