An American Student’s Encounters with Islam in Morocco

- By Jayla Lundstrom --

- 19 Jul 2016 --

Featured Contributor Jayla Lundstrom, a volunteer at the Zaouia Sidi Abdessalam Youth Center in Morocco, details her experience learning about Islam.

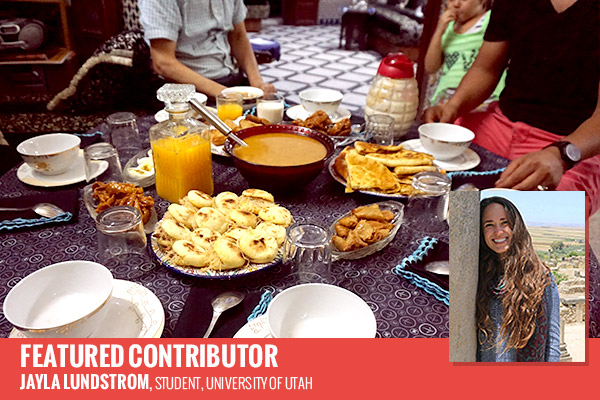

The tightly checkered black and white tiled walls stole my attention as I sat in a riad, deep in the old medina of Fes. A cool breeze blew through the courtyard where I sat with two other volunteers, our bellies full of chebakia, harira, and other various and mostly honey coated delights that I can’t pronounce. The man sitting across from us hugged his knees, his leathered skin hung from his bony features as he gently smiled, insisting that we eat more.

An American Student’s Encounters with Islam in Morocco[/tweetthis]

We had met this man only two hours prior. After exchanging a few mumbled words, we wove through the crowded souks and markets that smelled of raw meat, mint, and turmeric. Struggling to follow his nimble pace in the maze of tight, cool streets, we finally reached a modest looking brass gate that housed his extravagant eight bedroom riad. For the last two hours, we lounged on embroidered couches, attempting to follow his fast French as he told us about travels, Fes, and his family.

Like a lot of conversations that I have had in Morocco, from the village where I run a summer camp to the family break-fasts that I was invited to for Ramadan, the conversation shifted towards religion, and the old man suddenly became more serious. I’m always hesitant to openly discuss religion, and I grew uncomfortable as he began to share his beliefs. Little did I know that these casual conversations would expose me to a new perspective of Islam.

“Islam is a simple religion,” she added, “We pray five times a day to reconnect ourselves with God, and to remind ourselves to make the right decisions.”

The man explained to us how we are all Allah’s creation, making every being on Earth family. To him, extremism and violence aren’t possible because harming your own brothers and sisters isn’t fathomable. “Allah created Earth for all,” he stated as his small, black, and kind eyes gazed into mine. He continued, “If you create something beautiful, and someone deliberately tried to destroy your creation–how would you feel?”

His question seemed obvious, yet we all looked at each other as if we didn’t know the answer. “We would feel bad,” I answered with a sense of unease about my limited French vocabulary.

Judging from his content and eager face, we seemed to produce the precise answer he was looking for. He smiled gently, and responded: “Extremists and those who are violent towards others in any way are destroying Allah’s creation. He created Earth for all of us, we are all family, so why would you destroy Allah’s creation and harm your family?”

Not having a response, we sat in silence as he leaned towards us. With his hands on his knees and crevassed face gleaming, he asked us if we knew the meaning of Ramadan. We responded in mumbles. From having a similar conversation with some friends at the university, I had an idea, but was curious to see if the meaning transcended generations.

“Ramadan is for the poor,” he stated, echoing the explanation of my friends at the university. He explained how fasting for the full month allows one to feel hunger and feel thirst. It provides a sense of humility and forms empathy towards those who don’t have access to water or food. In a way, Ramadan equalizes humanity.

“God made us all different. However, Islam is about recognizing those differences and sharing what you were given to make society more equal,” he continued.

A week later, I was sitting in the classroom where I volunteer, reviewing household vocabulary in Darija, the local dialect, with one of the women from the community. Our conversation shifted from vocab towards the differences between family values in Morocco versus America. The soft-spoken woman, with kind winking eyes and a vibrant pink head scarf, was bewildered to hear that I lived away from my family. Once again, we began to discuss Islam: her beliefs, explanation for fasting, and view on terrorism were parallel to the man’s at the riad.

“Islam is a simple religion,” she added, “We pray five times a day to reconnect ourselves with God, and to remind ourselves to make the right decisions.”

Before I had the chance to engage in these random yet earnest conversations, my views of Islam were shaped by the biases of western media. I didn’t understand what it meant to live in a country that is characterized by its religious observances. I had never met a Muslim; I had never discussed the Quran with someone who practiced Islam; I had no idea what Islam meant to the diverse range of individuals who practiced it.

By listening to the beliefs of the people I have met in Morocco, I have uncovered for myself a simpler component of Islam and the communal life that surrounds it. Before I arrived in Morocco, my views of Islam were tied to political conflict and a foreign culture, not the morality and sense of community that I’ve witnessed here.