Florida Black Churches Combat Mandated Sterilization of Their History In Schools—They Teach It Themselves

- By Geoffrey Peters --

- 24 Oct 2023 --

“Whenever there has been any kind of movement, particularly in the African American community, it started in the house of God.” — Rev. Gaston Smith

What does a person suffering from amnesia do? Where does he or she go to find out something, anything about the forgotten past, the vanished identity, the answers to the questions, “Who am I?” “What happened?”

Generally, one is surrounded by loved ones and caregivers who gently try to jog the forgotten memories, as bit by bit unconsciousness evaporates, the clouds lift and memories—along with personhood and identity—return.

What does a community under threat of amnesia do? Where does it turn for answers to the questions, “Who are we?” “What happened?”

They, too, thanks to dedicated religious leaders, can go to a place where they are surrounded by loved ones and care-givers and where they can learn the truth of their history. That place: church.

Amnesia for Florida’s African American community set in with the passage of the 2022 “Stop Woke Act” which severely limited discussion of race and revised Black history, sanitizing the uncomfortable parts and rewriting others to the point where middle-schoolers were ordered taught “how slaves developed skills which, in some instances, could be applied for their personal benefit.”

Florida pastor Rev. Rhonda Thomas was as dismayed as many others at the darkness descending on the curriculum, but was not moved to action until a conversation with a voting rights activist ignited something. He said that once, long ago, the Black church had been the heartbeat of the community—“to the point that we became a threat, and that’s why we were bombed. When have we last been a threat?”

The question was a challenge. She said that, after thinking about it she decided, “I want to be a threat.”

Wielding the power of the Black church, the pastor created a nonprofit coalition of religious institutions, Faith in Florida, which bypass the system and teach Black history through what it calls “the lens of truth.”

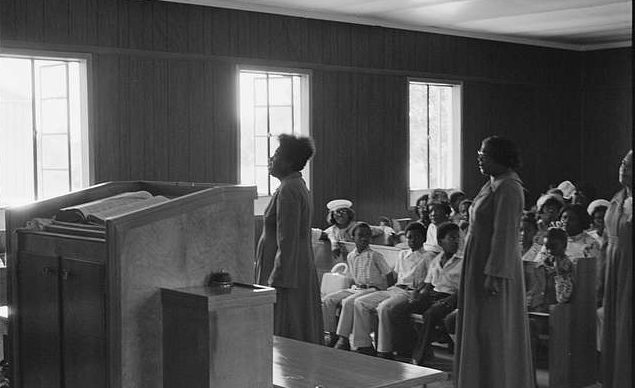

The amnesia befalling the Black community would be erased by its churches. At Friendship Missionary Baptist Church in Liberty City, Rev. Gaston Smith teaches congregants who are there to pray—and learn.

“Whenever there has been any kind of movement, particularly in the African American community, it started in the house of God,” Smith says from the pulpit. “We cannot be apathetic, we cannot sit back, we cannot be nonvocal. We have to stand our ground, because the Bible says we have to speak up for those that cannot speak up for themselves.”

Behind him television screens bear the legend, “BLACK HISTORY MATTERS.” After Smith reads a passage from Acts he dims the lights and shows a documentary about “an injustice that has taken place right here in the state of Florida many years ago.” A woman beaten as a teen in 1964 for being one of the first Black students at Gainesville High School, describes the atrocity and then says, “I stayed home about a week. And then I got up, and I told Dad to take me back to school. I said, ‘You know what, they’re just going to have to kill me, because I cannot let them win.’”

Faith in Florida gained traction and has spread quickly with over 260 religious institutions signing on since July, pledging to teach Black history. The roster of houses of worship is not restricted to Black congregations. Synagogues, Catholic churches and mosques have also raised their hands—some of them from outside of Florida.

The coalition rapidly developed an 11-chapter tool kit as a study guide and suggests books, essays, films and reports that more accurately cover the Black experience through history. Under the banner, “Black History Is American History,” the tool kit covers a lot of ground. In addition to recommending resources for children and adults, chapters entitled, “From Africa to America,” “Race, Racism & Whiteness,” “Racial Terrorism & Civil Unrest” and “Black Women in Leadership” give an idea of how much is encompassed—from pre-slavery all the way to our own time.

The website includes a statement from Executive Director Thomas: “One of the first things enslavers did was enact laws to criminalize our ancestors to keep them from reading. They feared that if the enslaved Africans read books, they could not suppress them. The slave masters knew what power books held. Those books had stories and knowledge of where our ancestors came from and who they used to be. Discovering this would disrupt the chattel slavery system they were trying to build.”

A passage in last year’s legislation “revising requirements for required instruction on the history of African Americans” particularly struck a nerve with Rev. Thomas: that education should be tailored so no student would feel guilt or “psychological distress” over past actions by members of the same race.

“If you want to look at who feels bad, I was born into this world as if it was designed for me to live feeling bad,” she says. “I don’t think any lesson should be taught to make anyone feel angry, but if it’s history, it’s history, right?”

Once you tell a person a bit about his or her forgotten past, the thirst to hear more is unquenchable. And so it is with the educational tool kit presented by Faith in Florida which is now fielding requests to establish an entire curriculum. Thomas who “had no idea it was going to go this far,” hopes to get to it by the second half of the school year.

At Friendship Missionary Baptist the lights are back on as the documentary ends. Rev. Smith says, “That documentary is not there so that you would get angry. But that documentary is there to remind the world, the nation, this state, that we will not go back where we’ve been.”

When you wake up from amnesia and know who you are, where you’ve come from and where you’re headed, it is indeed impossible to go back to that unknowing state.

And likewise, for a community, it’s impossible to ever allow forces to gather and conspire to bring about that state again.