New release from Pim Valkenberg on the 50-year legacy of Nostra Aetate.

Written by Joseph Preville and Julie Poucher Harbin for ISLAMiCommentary

Has Nostra Aetate – the Catholic Church’s declaration on relations with non-Christian religions — stood the test of time? Passed by a wide margin at the Second Vatican Council and promulgated on October 28, 1965 by Pope Paul VI, this powerful document rejected all forms of anti-Semitism and prejudice or hostility toward Muslims, Buddhists, and Hindus. The declaration encouraged Catholics “to recognize, preserve, and foster the good things, spiritual and moral, as well as the socio-cultural values found among the followers of other religions.”

Has ‘Nostra Aetate’ stood the test of time?[/tweetthis]

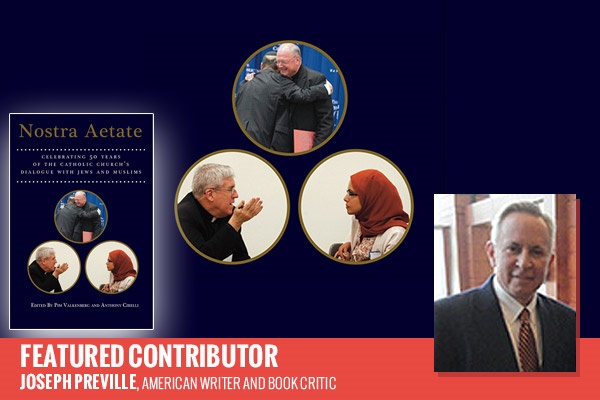

The collected papers of this conference form the basis of a new book published by The Catholic University of America Press: Nostra Aetate: Celebrating Fifty Years of the Catholic Church’s Dialogue with Jews and Muslims.

The book is edited by Pim Valkenberg, professor of theology and religious studies at The Catholic University of America, and Anthony Cirelli, associate director of the Secretariat for Ecumenical and Interreligious Affairs at the United States Conference of Catholic Bishops.

Valkenberg discusses Nostra Aetate’s impact and relevance today in this exclusive interview.

How significant is Nostra Aetate in the history of the Catholic Church? And, how revolutionary was it for its time?

I think that Nostra Aetate is quite significant in the history of the Church, since this is the first time the Catholic Church explicitly reflected on its relationship with other religions. The relationship with other religions was not on the original agenda of the council, and it was only scheduled on the program because Pope John XXIII was convinced that the Church should explicitly distance itself from the “teaching of contempt” that laid a heavy burden on the Church’s relationship with the Jewish people. That is, whenever the Church said something positive about its own mission and message, very often it went together with something negative about the Jewish people: they rejected Christ, read their Scriptures wrong, denied the grace of God, etcetera.

The original idea of Pope John XXIII was to write about the Church’s relationship with the Jewish people only, but bishops from the Middle East and Asia said that the Church’s relations with Islam and other religions should be included as well. (Pope John XXIII died during Vatican II and Pope Paul VI took over.)

Nostra Aetate was passed by 2,221 votes to 88 by the assembled bishops? What were the specific reasons for opposition to the document?

First of all, 88 is not a big number; it is less than a half percent. The French theologian Yves Congar wrote in “My Journal of the Council” that the opposition to the final document was much less than the opposition to several of its stages. Yet there were bishops who found the document unacceptable because it said something really new in its positive approach to other religions, and therefore they judged it was not in continuity with the venerated tradition of the Church (just like the document Dignitatis Humanae on human dignity and religious freedom). These are still the Vatican documents least liked by ultra-conservatives.

How influential was the tragedy of the Holocaust in the crafting of Nostra Aetate?

Very influential. Nostra Aetate was originally conceived as a document to improve the relationship with the Jewish people. It was after a meeting with the French Jewish historian Jules Isaac that Pope John XXIII decided to give the Secretariat for Christian Unity the assignment to craft a document that would help to overcome the theology that made the Holocaust possible. The “teaching of contempt” did not cause the Holocaust, but it had contributed to a European culture in which the Holocaust could become a grim reality. In that sense, you can say that the Holocaust occasioned the document.

Apart from the “teaching of contempt” that I just mentioned, the relationship between Catholics and Jews was characterized by super-sessionism, which is the idea that the Church had superseded the Jewish People in its covenantal relationship with God. Since God had started a new relationship by sending his own Son who sealed this relationship with his death on the cross, and since Jews did not want to accept this new reality, the Church was of the opinion that the Jewish people were no longer in a faithful relationship with God. Another important notion that needed to be corrected in Nostra Aetate was that the Jewish people took responsibility for killing God (Deicide), and therefore were liable and could be punished by the faithful. This led to pogroms in many parts of Europe during the late Middle Ages and the early Renaissance period. However, there have always been theologians who believed in the lasting validity of the covenant between God and the Jews, and this point of view finally prevailed, on the basis of Saint Paul’s letter to the Romans, chapters 9-11.

How would you characterize the historical relationship between the Catholic Church and Asian religions?

It is hard to characterize the relationship between two religions in one sentence, and it is even harder when we are discussing the religious reality in Asia that is so complex and knows so many different cultural and religious contexts. But if there is one notion that still burdens the relationship, it is the notion of mission. The history of mission efforts to most Asian countries has been connected with the history of colonialism and in my contacts with Hindu dialogue partners (for example) it became clear to me that they still wish for an official moratorium on missionary efforts in order for them to build trust and to engage in official dialogue with Catholics.

How would you characterize the attitude and relationship of the Catholic Church toward Islam and Muslims before Nostra Aetate? How did the document accelerate and deepen dialogue between Catholics and Muslims?

From the beginning the relationship between the Christian Churches, both in the West and in the East, and the new religion of Islam has been quite tense. This has partly to do with the rapid spread of Islam, and partly with the fact that this new religion claimed to be a confirmation and a return to the original revelation of God. Christians could not accept that claim — in a similar way Jews did not accept the Christian claim to be a new covenant partner with God — and therefore they characterized Muhammad as an imposter and his revelation as a fraud. While it is certainly true that there have been more dialogical encounters between Christians and Muslims, in most cases polemics and apologetics dominated the mutual relationships.

In the twentieth century a more positive approach to Islam began to be entertained by members of religious orders and mystically inclined scholars of Islam. Nostra Aetate could use these more positive approaches and build on them by acknowledging that Christians and Muslims together worship the one God, Creator of heaven and earth, and that they share an important part of the history that God began by calling Abraham. Muslims are also acknowledged in their veneration for Jesus and his virgin Mother. The positive tone of Nostra Aetate certainly built the basis for many dialogue initiatives that followed, often coordinated by the Pontifical Council for Interreligious Dialogue.

How did Nostra Aetate resonate in the United States?

The best way to see the influence of Nostra Aetate in the United States is to look at the dialogue initiatives taken by the US Conference of Catholic Bishops. It began with the Bishops Committee on Ecumenical and Interreligious Affairs together with the National Association of Diocesan Ecumenical Officers in the 1980s. In the beginning most of the attention was directed at ecumenical dialogues and the dialogue with different Jewish groups – even though some of these dialogues had already been initiated before the Second Vatican Council, for instance in the 1920s and 1940s. Outreach toward other religions began in the 1980s and a regular threefold regional dialogue with different Islamic organizations started in 1996. Dialogue with representatives of other religions, such as Hindus, Buddhists, Jains and Sikhs is less formalized, even though the fiftieth anniversary of Nostra Aetate in May 2015 and then the visit of Pope Francis to the United States in September 2015 served to solidify these relations and to start some new initiatives.

What ecumenical programs and initiatives did Nostra Aetate spark around the world?

There is, obviously, a lot going on in the world. Maybe the most important observation that I could make is to relativize our Western perspective: in many Asian and African countries dialogues and other forms of encounters have been going on long before Nostra Aetate, often initiated by missionaries. Often the non-Western rite Catholics are very engaged in these initiatives. This is one of the reasons why bishops and theologians from these countries were instrumental in crafting the text of the document. After its promulgation in 1965 the Catholic Church started to work together with the World Council of Churches and sometimes also with Evangelical groups.

In the West, we have seen the rise of a sizeable number of dialogue initiatives, some more theological in nature — such as the Catholic-Muslim Forum that was initiated by the Muslim signatories of the “Common Word document” — and others more spiritual in nature, including the initiatives of the InterMonastic Dialogue groups with Buddhists in Asia, or the World Day of Prayer for Peace initiated by Pope John Paul II in Assisi in 1986. At the same time grassroots dialogue is the necessary basis of the more official dialogue initiatives.

How has Pope Francis underlined and emphasized the importance of Nostra Aetate in the ecumenical work of the Catholic Church?

It has been clear from the beginning that interreligious dialogue is very important to Pope Francis, as can be seen in his unprecedented initiative to take a Jewish and a Muslim friend from Argentina with him when he went to visit Jordan and Israel. He also invited the presidents of Israel and Palestine to pray with him for peace. He also released a video message in which a Jew, a Catholic, a Hindu, a Buddhist and a Muslim all state that they believe in love. In the book that we published, Dr. James Fredericks has written more explicitly about the “dialogue of fraternity” that Pope Francis promotes, mainly in dialogue with Buddhists.

Do you think that Nostra Aetate, if introduced today, would still have been adopted?

That is a very interesting question!

On the one hand, I think it is certainly true that the religious landscape has changed so much that certain expressions that were quite new fifty years ago are now old-fashioned. For instance, Pope Paul VI founded a new Secretariat for non-Christians in 1964 but in 1988 its name was changed into the Pontifical Council for Interreligious Dialogue which sounds quite different. In that sense I think that the reality of religious pluralism is much more prominent now than it was fifty years ago, and a new council would certainly need to pay considerable attention to relations with other religions in the same way as it gets attention now in every papal visit.

On the other hand, I think that the third paragraph on the Church’s relations with Muslims would be considered naïve if it was introduced today. For instance, the idea that we should “forget the quarrels and hostilities of the past” and “work together to foster social justice, moral welfare, and peace and freedom for all humankind” is true now more than ever – if you read “forget” as “not repeat”, that is – but at present this statement could not have been written in this way after everything that has happened in the last fifteen years.

So, from my perspective, Nostra Aetate has succeeded in its primary goal, namely to improve relations between Catholics and Jews.

As far as the Church’s relationship with Islam, the situation is the most complex. On the one hand, there is a wealth of institutional contacts and so we are no longer strangers. Yet, my constant worry as a theologian is that we have made no progress at all with the main theological questions between us. Of course it would be naïve to think that we could solve these questions after fourteen centuries of disagreement. But if theological dialogue is not so much about agreeing with one another as it is about negotiating the differences and learning how to disagree in a fruitful and respectful way, I must say that we have not learned much. And finally, yes, there is the violence between us that makes me think that no European parliament today would adopt the text of the paragraph of Nostra Aetate on Islam.

I am very grateful that the Church still stands behind this text and I am grateful that it says a couple of things – including the conviction that Christians and Muslims together worship the One God — about which many Christians now feel justified to doubt. If a professor at an Evangelical college can be dismissed because she says that Muslims and Christians worship the same God (quoting Pope Francis, by the way) I am glad that Nostra Aetate said what it said fifty years ago.

What did you learn while researching the history of Nostra Aetate that you didn’t know before? Did anything surprise you?

The thing that struck me most when doing my research is that almost nobody could have foreseen this document when the Council started. In the volumes that summed up the wishes of the bishops concerning the matters that should be discussed, almost nothing about other religions came up.

Historians and political scientists have described the council as an event with its own logic, but Catholics believe that this must have been the work of the Holy Spirit. What surprises me, reading the document once again after fifty years, and after some twenty-five years of personal experience in dialogue, is how much we can still learn from this document and that is reason to celebrate. However, the fifty years since Nostra Aetate have brought us an awareness of the human, often violent, sides of religion as well and therefore we need to work harder to build bridges and to gain a better understanding of the problematic sides of religions as human phenomena.

Pim Valkenberg on 50-Year Legacy of ‘Nostra Aetate’;Its Impact on Catholic/Jewish/Muslim Relations https://t.co/d9IUZpYb2u @CatholicUniv

— Julie Poucher Harbin (@julieblog) June 20, 2016

ISLAMiCommentary is a public scholarship forum that engages scholars, journalists, policymakers, advocates and artists in their fields of expertise. It is a key component of the Transcultural Islam Project; an initiative managed out of the Duke Islamic Studies Center in partnership with the Carolina Center for the Study of the Middle East and Muslim Civilizations (UNC-Chapel Hill). This article was made possible (in part) by a grant from Carnegie Corporation of New York. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author(s).

This article originally appeared on ISLAMiCommentary.