by Krista R. Burdine and Emily Murdoch

Pope Francis’ visit to South Korea highlighted the Catholic Church’s weak presence in Asia and the Vatican’s commitment to Asian countries, particularly China

Sixty percent of the world’s population lives in Asia, but the Catholic Church only finds 12% of its church body there. As the Church faces declining attendance across Europe and the US, Asia has become the natural next place on which to focus expansion efforts. This initiative was determined by the new pope in his early days in the position.

The Challenge in the Asian Continent

In addition to Hindu and Muslim resistance across the continent, Protestant churches already present in the region provide further competition for those who might resonate with the Christian message. Often those Christian churches have better funding and work better at organizing local movements into churches. Many Protestant churches advocate a prosperity gospel message, which suggests that God will financially bless those who follow him; this especially appeals to many in Asia as they are experiencing growing economic stability.

Yet the strongest opposition comes direct from Beijing, where government leaders of the religiously atheist Communist nation insist on maintaining control of church leader appointments as well as pre-approving messages from the pulpit.

China and the Catholic Church have always had a difficult relationship. China has gone so far as to sever diplomatic relations with the Vatican in the 1950s. The historical faith of the Chinese people has been a mixture of Taoism and Buddhism, and many people did not take kindly to the arrival of Christianity. When the Communist Party came to power in China, there was a swift movement against churches, and even now, when being a Christian is permitted in China, one has to attend the official state churches. This has led to many churches being informed ‘underground’, which means that people meet informally at each other’s houses in order to practice their faith without any interference.

Of course, the last thing that Pope Francis would want to do is upset those in power in China, so instead of challenging China’s citizens to choose between loyalty to the state and loyalty to the Catholic Church, he insisted that the church did not want to approach China as a “conqueror,” but as a partner in an open dialogue. However, although many Chinese Catholics managed to travel to Korea, in order to see the Pope, many were prevented from leaving the country, and many Chinese newspapers and news television channels have barely reported on the Pope’s visit to Asia at all. The Pope’s lack of media attention has left many Chinese Catholics feeling left in the dust.

While no movement appears imminent that would ease the Pope’s path into China, the Pope did receive a small concession for his trip to South Korea last week. His charter jet was given permission to fly over China airspace on the way to its final destination. Pope John Paul II was forced to fly around the perimeter of the massive country when he traveled to Seoul in 1989–the last time a pope visited Asia.

Part of the challenge the church faces in China is that culturally, the construct of civic organization differs from the Western world. In the communist run country, all organizations and social leaders fall under the ultimate leadership of the government–which places itself as the ultimate authority. Since church leaders are considered social leadership figures, they are subject to this authority. The threat offered by any free church is that members acknowledge an authority higher than the government.

Easing the way into Asia

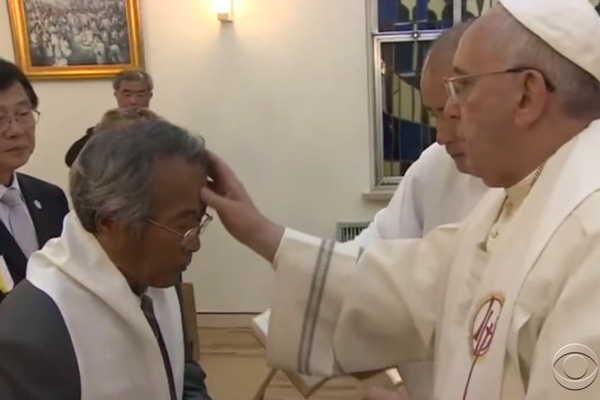

Pope Francis has made an effort to soothe concerns that the Catholic Church is coming to conquer Asia politically. During his South Korea visit, he spoke to a group of Catholic bishops representing more than 20 Asian countries. Some of them, including from China, Vietnam and North Korea, are not permitted to fall under the direct leadership of the Vatican, as their home countries do not permit the Vatican an absolute chain of command without governmental oversight. He stressed that the Church has no political plans for domination, just concern for the people’s eternal souls.

In his remarks, the pope acknowledged that the culture of the region requires a different approach than has been used in the Western world, and suggested looking for creative approaches to being Catholic in Asia. He also encouraged them, as representatives of a tiny minority averaging 3% of the Asian population, to hold fast to religious principles yet continually press for ways to be socially and culturally relevant in their communities.

Looking for Forward Movement

To affirm the Pope’s message that he considers Asia a top priority of his papacy, he has already scheduled another visit to the continent. He will visit Sri Lanka and the Philippines in January. This despite, or perhaps because of, his personal expectation that his term in office will last “a short time, two or three years, and then to the house of the Father.”

Part of the urgency for moving into Asia may be that its enormous population offers an exceptional possibility for return on church growth initiatives. Despite the opposition from China and other Asian countries, the Philippines and South Korea are places where the Catholic Church is growing and popular opinion toward the pope runs high.

As the Catholic Church seeks to reinvent itself for the Asian continent, Pope Francis is throwing himself wholeheartedly into making progress there for the first time in church history. He may have years yet to make headway, but his personal sense of urgency is prompting him to seek change sooner rather than later. Given his inexplicable appeal and the unifying demeanor that have already surprised the Western world, he may have a better chance than anyone before him of achieving at least part of his goal.